![]()

Public opposition to Temelin has quite a long history. Since the beginning of 80s, when the construction of Temelin first began, there have been several waves of oppostion. The first protests were organized by locals who were the first people to be dramatically effected by the construction: the villages of Krtěnov, Temelínec and Brezí were wiped-out and villagers resettled. Some people left immediately, others were forced out later, a few remained. Out of the 60 original inhabitants, only 7 still live in the village. The Pizinger family, who still remain, exemplify this struggle today.

They were bought out by CEZ 13 years ago, given low state prices for their property. And now that their house is destined for demolition this Spring, they will be forced from their homes with only a fraction of the house's value and will have lost their only trade - farming (they have been "relocated" to an urban setting which doesn't allow farm animals).

Reacting to these injustices, villagers attempted to publicly protest. Unfortunately, the oppressive Communist regime of the 80s didn't allow organized movements and, in effect banned their protests. They responded by continuing to demonstrate their disapproval individually. Their most common response was to send letters of protest which gained little sympathy or consideration from the government. The only reaction on the side of the establishment was an official explanation describing how the plant will play an important role in helping the future construction of socialism. Soon, the local opposition was completely silenced. There was little resistance in the years that followed because villagers felt it was nearly impossible to influence the government's centralized decision making policies.

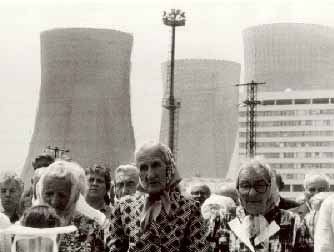

Fortunately, a big opportunity for campaigners opened up after the political changes in 1989. Supported by Austrians, the region experienced their first public and mass protests. Huge gatherings took place at the Temelin construction site. As a result, a tradition of opposition was created. The biggest protest; a festival at the main gate of the plant, occurred in 1991 which was attended by nearly ten thousand Czechs and Austrians!

This newborn movement did not go without detectable changes - in 1990, the regional government voted not to prolong the construction license for the 3rd and 4th reactors. This decision meant that the plant would now be half its original size. But despite this victory, chances for initiating a complete shut down of the project were vanishing quickly. Although the numbers involved in the movement were rising, their influence was decreasing due to time pressures.

The oppostion experienced its peak in 1990. During this time, testing

the new democracy with public protests was new and popular.  As

a consequence, many people actively participated in the campaign against

Temelin which, combined with temporary hesitation on the part of the state

institutions, greatly influenced decision makers. However, numbers began

decreasing monthly as people lost interest in participating in large scale

demonstrations. As a consequence, decision makers became more self-assurred

and less fearful of public pressure. CEZ, the Czech electricity utility,

ignoring the desires of the people, continued the construction of the plant,

pretending its completion was never in question.

As

a consequence, many people actively participated in the campaign against

Temelin which, combined with temporary hesitation on the part of the state

institutions, greatly influenced decision makers. However, numbers began

decreasing monthly as people lost interest in participating in large scale

demonstrations. As a consequence, decision makers became more self-assurred

and less fearful of public pressure. CEZ, the Czech electricity utility,

ignoring the desires of the people, continued the construction of the plant,

pretending its completion was never in question.

It was not long before this second wave of opposition, discouraged by polititians who still made decisions regardless of public opinion, began to withdraw and diminish. With no culture of opposition, most people preferred to go back to their private lives than continue resisting a government which didn't seem to be listening.

In the middle of 1992, the government made their final decision on Temelin's future. These decisions again challenged opponents of the plant and, in response, a third wave of oppostion was created. This time, its core was formed by a wide coalition of several dozens of environmental organizations. Their aim was simple: to convince the government to reject Temelin. They organised actions, petitions, public debates, open letters and other media events.

The newly elected (1992) government, lead by recent Prime Minister Klaus, was not interested in public opinion at all. Most requests for debates were simply ignored, petitions were not even formally answered, and open letters were thrown to the dust bins. By autumn 1992, despite clear opposition and obvious alternative resources, all ministers had agreed that Temelin was necessary and the best solution.

Studies had proven Temelin was not the least cost solution to the Czech Republic's energy needs as claimed by the nuclear establishment and ministers of government. Even though these results were published in papers and shown on TV, the ministers were already decided. In a formal decision in March 1993, all 18 voted in favor of Temelin. The announcement of this decision had a killing affect on the anti-nuclear movement - almost all the groups cooperating in the coalition gave up, thinking that further efforts would be a waste of time and resources. Consequently, they began focusing on other winable issues. After another battle lost, only a few decided to continue the war against Temelin.

Those few, still bravely opposing the plant, realized that without Western players (i.e., ExIm Bank and Westinghouse) in the project would be defeated. Therefore, a holistic strategy using internationals to pressure the Western players and a strong local civic movement with direct actions at its best targeting the Ministers at home was taken up by the opposition. As for western participation, the U.S. multinational corporation, Westinghouse, eventually won the contract for Temelin and formed a partnership with CEZ to upgrade Soviet technologies. The desire for western technology was inter-linked with a need for western money to pay for the modernization.

Westinghouse offered to secure finances through loan guarantees provided by U.S. Export-Import Bank. Thus, both needs - technical and financial - were met by the United States. One of the campaign highlights was the move to stop Ex-Im's financing of the construction of Temelin in 1994. Extensive lobbying at the U.S. Congress, whose members had the power to reject Ex-Im's decision, took place. In February and March 1994, with the help of several U.S. organizations, representatives of both Austrian and Czech movements opposed to Temelin travelled to the U.S. After many exhausting weeks in Washington, and despite the support of fifty Congressional representatives, the Ex-Im headquarters confirmed their decision to provide money for Temelin.

Today, there is a stronger focus on supporting the civic/direct action movement. The direct action movement, which continues to grow, represents historically the fourth wave of opposition to Temelin. Our first blockade of the Temelin site took place in May 1993, with about 50 participants blocking one of the gates for a few hours. All were arrested. Nevertheless, it brought wide media attention to the problem of Temelin. Then, in the summer, a protest camp was organized for the month of July. Both actions - blockades and camps - became the cornerstones of the movement.

Now, every year, a blockade and protest camp is organized. As the number of participants at the blockades grow (1993 - 50, 1994 - 150, 1995 - 250, 1996 - 350), and the length of the blockade increases (in 1996, it lasted 72 hours) these actions become more and more effective, making the life of nuclear proponents difficult. Furthermore, the yearly protests attract a considerable amount of public attention to the problem.

The blockades have also been supported by many well-known personalities : several singers, writers, and politicians (including Petr Pithart, former Prime Minister and recent Chair of Senate, and Petra Buzkov, the vice-chair of the House of representatives). We believe that the resistance will continue to grow. In fact, we are expecting at least 800 people at the blockade this July 1997. Everyone who wants to help and is willing to respect the non-violence guidelines, is welcome.

![]()

Resistance | Brain Food | The Players | '97Blockade | Links | CEB | SPACE